I actually quite like Go. Sure, it's not perfect, but I really like how brutally simple it is. There's very few frills, and this makes code easy to understand, most of the time.

One of the things I find really interesting about Go is how it implements string comparsions. Let's say you're building an internet-facing application with user accounts. The site doesn't matter so much as long as there's some user input that must be checked for validity. It could be a discount code, or perhaps you want to check whether a particular username exists already. The crucial point is that, for whatever reason, you've decided to do this validation in Go1.

At some point you may need to compare two strings, either to authenticate a user or for some other reason. This is pretty simple in Go:

var luckyGiveaway = "GIMMEFREESTUFF"

type Order struct {

// ...

DiscountCode string

}

func validateDiscount(order *Order) int {

// Compare special discount code.

if order.DiscountCode == luckyGiveaway {

return 100

}

var discount int

// ...

return discount

}

Here the code compares the DiscountCode string on the order object to the

special, and probably secret, luckyGiveaway discount code.

How would you compare two strings? Seems pretty simple, right? Maybe you'd start by comparing the length, because if the lengths are different then obviously the strings are different. But what then? Well, all the characters need to match2. To check equality we might compare characters from our two strings, one at a time. Let's compare "GIMMESOMETHING" with "GIMMEFREESTUFF". We compare the characters "G", "I", "M", "M", and "E" from each string and find they all match. We then compare "S" with "F" and find they don't, so we know the strings aren't the same.

This approach to string comparison has linear computational complexity with

respect to the length of the string. If a string has n characters, we can

expect at most n comparisons, one for each character, in order to know whether

the two strings are equal. Each of these comparisons eats up some CPU cycles,

and as a result it takes longer to detect different strings if the first

mismatched character appears later in the string. For example, our process above

takes longer to identify that "aaaaaa" and "aaaaab" are not equal than "aaaaaa"

and "abbbbb".

We can leverage this and implement a timing attack to recover the value of

luckyGiveaway. Using a string with the same length as luckyGiveaway, we try

all possible values of the first character in the string. When we use the

correct first character, the validation logic will take marginally longer, since

it must check the second character as well as the first. We can detect this

subtle difference in timing and from it infer when we've used the correct

character. We continue to the second character with the same approach, then the

third, until we've recovered the entire value of luckyGiveaway.

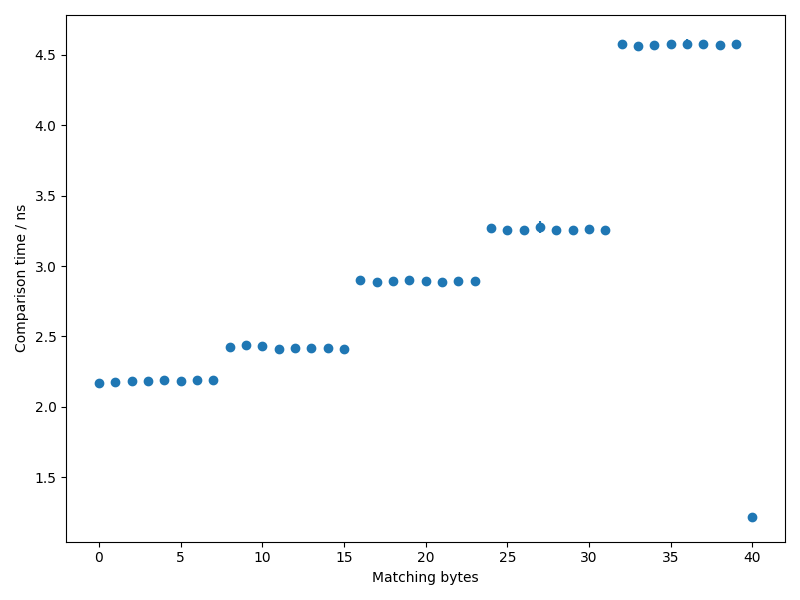

We can create a set of benchmarks in Go to demonstrate this behaviour. Plotting the timings as a function of the number of characters produces the following graph:

This is a little unexpected. Based on our assumptions above, we'd expect a steadily increasing series of points, rather than the clusters of identical times we see here. This suggests that comparing "GIMMEFREESTUFF" with "GIMMEFREESTUF\$" takes just as much time as comparing it to "GIMMEFREE\$\$\$\$\$".

But why? How does Go actually compare strings? Let's compile the example above to Go assembly using Godbolt and find out:

main_validateDiscount_pc0:

TEXT main.validateDiscount(SB), ABIInternal, $32-8

CMPQ SP, 16(R14)

PCDATA $0, $-2

JLS main_validateDiscount_pc65

PCDATA $0, $-1

PUSHQ BP

MOVQ SP, BP

SUBQ $24, SP

FUNCDATA $0, gclocals·wvjpxkknJ4nY1JtrArJJaw==(SB)

FUNCDATA $1, gclocals·J26BEvPExEQhJvjp9E8Whg==(SB)

FUNCDATA $5, main.validateDiscount.arginfo1(SB)

FUNCDATA $6, main.validateDiscount.argliveinfo(SB)

PCDATA $3, $1

MOVQ 8(AX), CX

CMPQ main.luckyGiveaway+8(SB), CX

JNE main_validateDiscount_pc46

MOVQ (AX), AX

MOVQ main.luckyGiveaway(SB), BX

PCDATA $1, $1

CALL runtime.memequal(SB)

TESTB AL, AL

JNE main_validateDiscount_pc54

main_validateDiscount_pc46:

XORL AX, AX

ADDQ $24, SP

POPQ BP

RET

main_validateDiscount_pc54:

MOVL $100, AX

ADDQ $24, SP

POPQ BP

RET

main_validateDiscount_pc65:

NOP

PCDATA $1, $-1

PCDATA $0, $-2

MOVQ AX, 8(SP)

CALL runtime.morestack_noctxt(SB)

PCDATA $0, $-1

MOVQ 8(SP), AX

JMP main_validateDiscount_pc0

This looks complicated, but the key point is that the implementation calls

runtime.memequal with variables stored in the registers AX

(order.DiscountCode), BX (luckyGiveaway) and CX (the number of bytes to

compare).

For the amd64 architecture, runtime.memequal is implemented

here.

Much of the implementation lives in a helper function named memeqbody. The

comments inside memeqbody give some big clues to what's going on:

TEXT memeqbody<>(SB),NOSPLIT,$0-0

CMPQ BX, $8

JB small

CMPQ BX, $64

JB bigloop

# ifndef hasAVX2

CMPB internal∕cpu·X86+const_offsetX86HasAVX2(SB), $1

JE hugeloop_avx2

// 64 bytes at a time using xmm registers

PCALIGN $16

hugeloop:

CMPQ BX, $64

JB bigloop

MOVOU (SI), X0

MOVOU (DI), X1

MOVOU 16(SI), X2

This suggests that the implementation has been optimised to take advantage of SIMD instructions on processors that support them. SIMD, or single instruction, multiple data, is a CPU feature that allows the processor to work on multiple pieces of data in a single operation. The classic use-case here is in high performance computing, or HPC, where the CPU is required to crunch large numbers of operations in parallel.

SIMD support on Intel amd64 chips has had various iterations since its introduction in 1997. The assembly here references AVX2, or Advanced Vector Extensions 2. These registers can each hold a massive 256 bits, or 32 bytes, of data, allowing them to crunch four double-precision floating point numbers in one instruction.

The assembly listing mentions comparing 64 bytes at a time, using two pairs of AVX2 registers, but our strings aren't that long, so why are we still seeing the clustered timings in the graph above? Once again, the assembly contains the answer:

bigloop_avx2:

VZEROUPPER

// 8 bytes at a time using 64-bit register

PCALIGN $16

bigloop:

CMPQ BX, $8

JBE leftover

MOVQ (SI), CX

MOVQ (DI), DX

ADDQ $8, SI

ADDQ $8, DI

SUBQ $8, BX

CMPQ CX, DX

In this case, it turns out we're not using SIMD instructions. Instead, the runtime packs our strings into eight-byte registers and compares these instead. This explains the clusters of timings in the graph, which form groups of eight.

There's one last nifty optimisation performed by runtime.memequal. On the far

right of the graph, where all 40 characters of the strings match, the benchmark

is much lower than any of the other results in our data. The reason for this is

revealed in the first few lines of runtime.memequal:

TEXT runtime·memequal<ABIInternal>(SB),NOSPLIT,$0-25

// AX = a (want in SI)

// BX = b (want in DI)

// CX = size (want in BX)

CMPQ AX, BX

JNE neq

MOVQ $1, AX // return 1

RET

neq:

MOVQ AX, SI

MOVQ BX, DI

MOVQ CX, BX

JMP memeqbody<>(SB)

Before the implementation does anything else, it first compares the pointers to the two strings. If these match, the strings must be equal, so the function returns early. Because of the way the expected and actual strings are constructed in the benchmark, when the two are equal they will in fact be the same string.

So, does this mean that string comparison in Go is invulnerable to timing attacks? No. For starters, we've only examined the amd64 architecture. Whilst it's probable that others will provide similar functionality, we shouldn't rely on this. Besides, the optimisations here only make timing attacks harder, not impossible. It would still be theoretically possible to brute force our way through the roughly $10^{20}$ possible eight-byte character combinations, even if the time required was much greater.

Given all of this, how can we safely compare two strings in Go? Fortunately, the

standard library has our back. The

crypto/subtle package contains various

functions to compare various Go primitives in constant time. In the case of

arrays of bytes, the implementation is kind of interesting:

func ConstantTimeCompare(x, y []byte) int {

if len(x) != len(y) {

return 0

}

var v byte

for i := 0; i < len(x); i++ {

v |= x[i] ^ y[i]

}

return ConstantTimeByteEq(v, 0)

}

func ConstantTimeByteEq(x, y uint8) int {

return int((uint32(x^y) - 1) >> 31)

}

So after checking the length, the implementation XORs corresponding bytes in the two strings, ORing the result into a collector byte. If this collector byte is zero, the two strings match. Even when performing this last comparison, the operations are constructed in such as way to ensure they run in constant time, preventing any possibility of a timing attack on the comparison.